Frederick Anderson

See Sydney George Dixon

Frank Brown

Frank Brown's grandson Roger contacted me via this website to buy a copy of Southborough War Memorial, and wrote: "It really is a fitting memorial to all those brave folk. I only wish I had known about it earlier. It took me many, many visits to the TW Ref Lib'y to find my first picture of my grandfather Frank Brown!" He has since kindly sent a potted biography of his grandfather to add to this page :

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Alfred John Diggens

Frank Chapman writes in 2009 in his Warwick Notebook page in The Kent & Sussex Courier of Alfred Diggens' father: HEADMASTER'S 35 YEARS IN CONTROL AT SCHOOL - Boys who wrote left-handed had no problem at King Charles School, Tunbridge Wells, 100 years ago. The Headmaster, Mr WA Diggens, experimented with ambidextrous training in 1904, issuing copy books to all classes for practice in left-handed writing. Mr Diggens, who retired in 1914 after 35 years as head, has been described as "a born organiser and stickler for details... a thorough scholar, and skilful imparter of knowledge, a firm disciplinarian but a humane and humorous master." Diggens' scripture lessons were said to be "full of profit and delight". He was a "mighty host in English grammar" but the "slacker's most pitiless foe". His experimental introduction of shorthand and book-keeping classes as additional skills for his boys upset a school inspector who regarded them as "of little educational value".

Sydney George Dixon

Beryl Fulker, Sydney's younger sister, writes that since reading the book, she has discovered some other family connections with those on the War Memorial: Their father William was the nephew of Ben Pown's mother Selina (nee Dixon), making Ben Pown and Sydney Dixon first cousins once removed. Also, Frederick Anderson was uncle to Beryl and Sydney's cousin. Lastly, Beryl's cousin-in-law was related to Albert Victor Gainsford and George Arthur Gainsford.

Funnell family members

A descendant of the Funnell family members commemorated, Jenny Lewis, writes: "Thanks for the book, it's great to see these guys as real people with real stories rather than faceless names. I thought you would like to know that I have located all the Funnells on my tree. They were actually quite closely related. Frank was my great grandfather's brother. Stephen A was his first cousin. Frederick and Ernest were sons of another first cousin. Henry G and Alfred G were sons of Frank's father's first cousin. I am not sure what the usual terminology is, but I would call both sets of brothers 'second cousins' of Frank. Interesting to note is that according to our research, Frederick was born with the surname 'Pronger', his mother's maiden name, and it looks like he was born before her marriage to Percy, so I think he may have been another man's son, but was brought up as Percy's and changed his name accordingly. For visit to Stephen's grave, click here.

The following is an extract from an account of the battle in which Frederick Funnell lost his life, compiled by Mr H Kershaw, of Hove, and included here with his kind permission:

On the night of the 17 August … the 6th Airborne Division pursued the Germans as quickly as possible and on the evening of the 18 August the 3rd and 5th Parachute Brigades arrived at Goustranville – some 4200 fighting men. The 3rd Parachute Brigade was ordered to attack at once and to clear the enemy from the land between Goustranville and the small river passing by Putot-en-Auge. This they did and in the small hours of the morning of 19 August the 5th Parachute Brigade was ordered to pass through the 3rd Brigade, cross the river and capture Putot-en-Auge. The 5th Brigade which included the 7th, 12th and 13th Parachute Battalions were the troops primarily engaged here.

In the early hours of the 19 August the 13th Parachute Battalion was ordered to lead the advance and to cross the river by the northern bridge. They were late in reaching the bridge because the land between Goustranville and the bridge had not been completely cleared of enemy troops. When they arrived at the bridge they found that it had been so heavily damaged that it was not possible for the entire Brigade to cross. The Battalion therefore halted without crossing and turned to the south. In the meantime, the 7th Battalion, which had been following, learned that the northern bridge could not be used and also that there was an undamaged footbridge to the south. They therefore changed direction, headed for, and crossed by this footbridge, followed by the 12th Battalion and finally by the 13th Battalion when it arrived.

The 7th Battalion crossed the railway line by the Putot station at 0500 hours and met very heavy fire in the rectangular field to the east of the station. They were held up for some time but reached their objective, an orchard to the north of Putot, by 0700 hours.

The 12th Battalion followed behind, and to the right of the 7th Battalion, but because of the delays caused by the failure to cross the northern bridge, they did not arrive at the Form Up Point until 0500 hours. They were then ordered to attack up the hill towards the Church, a task originally intended for the 13th Battalion. The village was captured by 0700 hours on 19 August. For the remainder of that day the Battalion stayed in the village suffering heavy casualties from mortar and shell fire which also caused heavy destruction to buildings in the village.

The 13th Battalion, the last to cross the footbridge, was originally intended to capture the village. Because of the delay in their arrival they were ordered to pass through the positions held by the 7th and 12th Battalions, and attack the high ground, known as Hill 13, on the far side of the village. The first crest of this hill was captured and held against German counter attack. The second crest was captured but could not be held. It was finally captured by another Brigade of ground troops on the night of 19 August. The 13th Battalion suffered very heavy casualties during this attack. This engagement at Putot was the first major battle to be fought during the German retreat, which eventually ended in Germany.

On the night of the 17 August … the 6th Airborne Division pursued the Germans as quickly as possible and on the evening of the 18 August the 3rd and 5th Parachute Brigades arrived at Goustranville – some 4200 fighting men. The 3rd Parachute Brigade was ordered to attack at once and to clear the enemy from the land between Goustranville and the small river passing by Putot-en-Auge. This they did and in the small hours of the morning of 19 August the 5th Parachute Brigade was ordered to pass through the 3rd Brigade, cross the river and capture Putot-en-Auge. The 5th Brigade which included the 7th, 12th and 13th Parachute Battalions were the troops primarily engaged here.

In the early hours of the 19 August the 13th Parachute Battalion was ordered to lead the advance and to cross the river by the northern bridge. They were late in reaching the bridge because the land between Goustranville and the bridge had not been completely cleared of enemy troops. When they arrived at the bridge they found that it had been so heavily damaged that it was not possible for the entire Brigade to cross. The Battalion therefore halted without crossing and turned to the south. In the meantime, the 7th Battalion, which had been following, learned that the northern bridge could not be used and also that there was an undamaged footbridge to the south. They therefore changed direction, headed for, and crossed by this footbridge, followed by the 12th Battalion and finally by the 13th Battalion when it arrived.

The 7th Battalion crossed the railway line by the Putot station at 0500 hours and met very heavy fire in the rectangular field to the east of the station. They were held up for some time but reached their objective, an orchard to the north of Putot, by 0700 hours.

The 12th Battalion followed behind, and to the right of the 7th Battalion, but because of the delays caused by the failure to cross the northern bridge, they did not arrive at the Form Up Point until 0500 hours. They were then ordered to attack up the hill towards the Church, a task originally intended for the 13th Battalion. The village was captured by 0700 hours on 19 August. For the remainder of that day the Battalion stayed in the village suffering heavy casualties from mortar and shell fire which also caused heavy destruction to buildings in the village.

The 13th Battalion, the last to cross the footbridge, was originally intended to capture the village. Because of the delay in their arrival they were ordered to pass through the positions held by the 7th and 12th Battalions, and attack the high ground, known as Hill 13, on the far side of the village. The first crest of this hill was captured and held against German counter attack. The second crest was captured but could not be held. It was finally captured by another Brigade of ground troops on the night of 19 August. The 13th Battalion suffered very heavy casualties during this attack. This engagement at Putot was the first major battle to be fought during the German retreat, which eventually ended in Germany.

Albert Victor Gainsford

See Sydney George Dixon

George Arthur Gainsford

See Sydney George Dixon

William Henry Godsmark

I visited the grave of William Henry Godsmark at Lijssenthoek in September 2012.

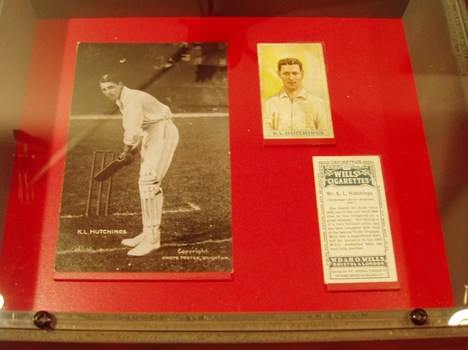

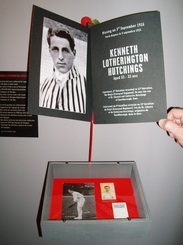

Kenneth Lotherington Hutchings

The excellent Historial de la Grande Guerre Museum in Peronne. Somme region of France, has mounted an exhibition (19 April - 25 November 2012) to the Missing of the Somme. There are over 72,000 missing named on the Thiepval Memorial. Kenneth Lotherington Hutchings is one of the 141 men honoured in the exhibition.

William Roy McMillan

William Roy McMillan was known as Roy to his family. His twin brother Mr KI McMillan writes that the Kent and Sussex Courier extract quoted in SWM was mistaken, in that Roy had nothing to do with the Ground Nuts Scheme in East Africa. Mr McMillan writes further: "Roy left for Australia in 1950 under the £10 Pom scheme, working his way across the country and finishing in Darwin, where he joined the Regular Australian Army, who flew him back to Melbourne for training. He was then sent to Japan, and Korea in 1952. Whilst patrolling the forward line against Chinese forces, his patrol clashed with another Australian patrol, resulting in casualties including Roy's tragic death by "friendly fire". Killed in action. Roy is buried in Pusan, South Korea, in the Australian section of the Commonwealth War Cemetery."

Henry Moon

I visited the grave of Henry Moon at Lijssenthoek in September 2012:

Ronald William Albert Moon

Private Moon, 2nd Bn, Parachute Regiment, who died 20 September 1944, age 23. Ronald Moon's sister has contacted the author and asked her to correct the error made in reporting that Ronald's mother was Mrs Winifred Moon. Mrs Winifred Moon was the step-mother of Ronald and his sister, and the mother of their brother Patrick. Ronald and his sister lived happily with their grandparents and aunt at 63, Meadow Road, Southborough before their father re-married and they moved to Charles Street. Their own mother was born May Lucy Lyford and was living in Canada at the time of Ronald's death.

Mr Martin Kirkham was a friend of Ronald Moon's younger brother Patrick (Pat); they grew up together in Southborough in the 1940s and 1950s, Patrick Moon in Charles Street, and Martin Kirkham in Edward Street. They went to school respectively at Judd and Skinners'. Pat often talked to his friend Martin about Ronny (known to his army colleagues as Ronny, to the family as Ron), who had been posted as "missing in action" until the end of the war six months later, when it was confirmed that he had lost his life. Pat was deeply affected by his brother's death, and the uncertainty which preceded the news.

The following is from an account of the part played in the Battle of Arnhem in September 1944 by B Company of the 2nd Battalion, The Parachute Regiment, kindly sent to me by Martin Kirkham:

'What was left of the original British main force now pulled back and regrouped around Brigade and Battalion HQs and the adjacent houses. In this last position, Private Don Smith took cover in a house next to Hofstraat, the house of Dr Van Niekirk. By now, most of the remaining men of B Company had dug in, in the garden behind the house. Don Smith: "We defended the building with spasmodic fire fights developing. At about 2pm (I am uncertain about the time), Regimental Sergeant Major Jerry Strachan opened fire with a sub machine gun from the top window aiming down the street. The Germans retaliated and all hell broke loose. The RSM rushed down the stairs and told us to get out fast. I rushed towards the rear window when there was a tremendous explosion. I felt myself being propelled through the air, in sort of a slow motion. Suddenly I hit the garden wall. Ronny Moon, who had been in the garden, came up to me and asked if I was all right. I said I was. I was only slightly wounded, and losing some blood. Ron then took his Bren gun, and ran towards the house. He was going into a downstairs room when he was hit and killed instantly by a tracer bullet through the head."

Norman Dellar was also in the garden, and had taken cover in one of the slit trenches near the house. He remembers that when he looked up he saw Ronny Moon lying there. Dellar: "His hand seemed to reach out to me, quite peacefully. I seem to remember his hand, as he was wearing a remarkable ring." Pte Ronald Moon's body was never found after the war.

Mr Martin Kirkham was a friend of Ronald Moon's younger brother Patrick (Pat); they grew up together in Southborough in the 1940s and 1950s, Patrick Moon in Charles Street, and Martin Kirkham in Edward Street. They went to school respectively at Judd and Skinners'. Pat often talked to his friend Martin about Ronny (known to his army colleagues as Ronny, to the family as Ron), who had been posted as "missing in action" until the end of the war six months later, when it was confirmed that he had lost his life. Pat was deeply affected by his brother's death, and the uncertainty which preceded the news.

The following is from an account of the part played in the Battle of Arnhem in September 1944 by B Company of the 2nd Battalion, The Parachute Regiment, kindly sent to me by Martin Kirkham:

'What was left of the original British main force now pulled back and regrouped around Brigade and Battalion HQs and the adjacent houses. In this last position, Private Don Smith took cover in a house next to Hofstraat, the house of Dr Van Niekirk. By now, most of the remaining men of B Company had dug in, in the garden behind the house. Don Smith: "We defended the building with spasmodic fire fights developing. At about 2pm (I am uncertain about the time), Regimental Sergeant Major Jerry Strachan opened fire with a sub machine gun from the top window aiming down the street. The Germans retaliated and all hell broke loose. The RSM rushed down the stairs and told us to get out fast. I rushed towards the rear window when there was a tremendous explosion. I felt myself being propelled through the air, in sort of a slow motion. Suddenly I hit the garden wall. Ronny Moon, who had been in the garden, came up to me and asked if I was all right. I said I was. I was only slightly wounded, and losing some blood. Ron then took his Bren gun, and ran towards the house. He was going into a downstairs room when he was hit and killed instantly by a tracer bullet through the head."

Norman Dellar was also in the garden, and had taken cover in one of the slit trenches near the house. He remembers that when he looked up he saw Ronny Moon lying there. Dellar: "His hand seemed to reach out to me, quite peacefully. I seem to remember his hand, as he was wearing a remarkable ring." Pte Ronald Moon's body was never found after the war.

James Hooper Dawson Nish

In January 2011 I had the opportunity to visit, for the first time, the town of Albert, in the Somme. I was able to visit and pay my respects at the grave of James Hooper Dawson Nish, who died aged 20, and is buried in the Albert Communal Cemetery Extension (further details in Southborough War Memorial). When I got home, I googled for this name, as I find that since I first researched the book, there is ever more information available online. I found the following on the University of Glasgow website, which must surely refer to a relative of James, as his mother is named on the Commonwealth War Grave Cemetery website as Jamima Hooper Dawson Nish, and he was born in Wigtownshire:

James Hooper Dawson (1806-1861)

The son of a farmer and landed proprietor, James Hooper Dawson was born in the parish of Morebattle, Roxburghshire, on 2 April 1806. He was a barrister by profession, but also edited the Kelso Chronicle and published two books, An Abridged Statistical History of Scotland (1853) and The Abridged Statistical History of the Scottish Counties (1862). He and his wife Barbara lived in Kelso with their six daughters. He was appointed examiner for the Dumfries District in 1855, and continued to serve as examiner until he died, aged 55, in 1861.

James Hooper Dawson (1806-1861)

The son of a farmer and landed proprietor, James Hooper Dawson was born in the parish of Morebattle, Roxburghshire, on 2 April 1806. He was a barrister by profession, but also edited the Kelso Chronicle and published two books, An Abridged Statistical History of Scotland (1853) and The Abridged Statistical History of the Scottish Counties (1862). He and his wife Barbara lived in Kelso with their six daughters. He was appointed examiner for the Dumfries District in 1855, and continued to serve as examiner until he died, aged 55, in 1861.

Ben Pown

See Sydney George Dixon

Thomas Arthur Vinall

I visited the grave of Thomas Arthur Vinall at Lijssenthoek in September 2012.

Maurice Carter Voile

Great-grandson Oliver Davey has kindly supplied the following on behalf of the family: Maurice Carter Voile was born in Cheltenham on 11th January 1893 to George Stephenson Voile, a coal merchant, and Ellen Louise Carter. George died in 1904 and in 1912 Maurice moved to Canada with his sister and mother to be nearer his older brother who had married and emigrated two years earlier. Whilst the other family members stayed in North America Maurice sailed back to England to marry his childhood sweetheart, Winifred Olive, in 1914.

On attaining the age of 21 he had access to his father’s inheritance, which he used to purchase Ivy House Farm on Pennington Road, Southborough, Kent. Their only child, a daughter called Joan, was born in July 1915 in the farmhouse. However, with no end in sight to the Great War Maurice sold the farm, which went to auction on 24th March 1916, and in May 1916 he joined the Machine Gun Corps, heavy branch. Following training in Bisley, Surrey he moved to Elveden, Norfolk where Lord Iveagh had provided land so that tank crews could be trained in secret. Early recruits into tank crews were men with mechanical skills, which Maurice would have acquired operating heavy farm machinery.

Maurice left Southampton for Le Havre on 16th August 1916 and moved up to camps on the Somme. The very first use of tanks was during the Battle of Flers-Courcelette on 15th September, part of the Somme offensive in which C Battalion took part. The family can’t be sure if Maurice was involved in the first action as the records were destroyed during the Blitz. However, if he wasn’t directly involved he would almost certainly have been in the reserves.

The next action Maurice was known to be involved with was a combined attack by British and Canadian forces on 9th April 1917 near Arras. Maurice and the crew of Tank C39 were charged with advancing towards a particular German stronghold, known as the Harp. Tank C39 was a Mark II tank, designed for training purposes and fitted with only unhardened armour. They were never meant for combat but with the delay of the Mark IV a number were used in the Battle of Arras. What happened is described in David Fletcher's book ‘Tanks and Trenches’. 2nd Lt Cameron (C39) found a gap in the attack where the infantry had lost touch. He engaged the enemy with Lewis gun fire until the infantry had time to come up and consolidate. During this time he routed an enemy machine gun crew and captured their gun. A little later the tank received a direct hit, killing one and wounding three of the crew. After attending to the wounded, Lt Cameron handed five of his Lewis guns and ammunition to the infantry. The man killed was Maurice Carter Voile and his comrades buried him near where he fell. Despite the gains of the first day the British were unable to exploit the situation and force a major breakthrough. Eventually the ground that had been gained on 9th April, with the exception of Vimy Ridge, was recaptured by the Germans.

After the war Maurice’s body was moved to its final resting place at the British Cemetery at Tilloy-Les-Mofflaines where the grave is maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

On attaining the age of 21 he had access to his father’s inheritance, which he used to purchase Ivy House Farm on Pennington Road, Southborough, Kent. Their only child, a daughter called Joan, was born in July 1915 in the farmhouse. However, with no end in sight to the Great War Maurice sold the farm, which went to auction on 24th March 1916, and in May 1916 he joined the Machine Gun Corps, heavy branch. Following training in Bisley, Surrey he moved to Elveden, Norfolk where Lord Iveagh had provided land so that tank crews could be trained in secret. Early recruits into tank crews were men with mechanical skills, which Maurice would have acquired operating heavy farm machinery.

Maurice left Southampton for Le Havre on 16th August 1916 and moved up to camps on the Somme. The very first use of tanks was during the Battle of Flers-Courcelette on 15th September, part of the Somme offensive in which C Battalion took part. The family can’t be sure if Maurice was involved in the first action as the records were destroyed during the Blitz. However, if he wasn’t directly involved he would almost certainly have been in the reserves.

The next action Maurice was known to be involved with was a combined attack by British and Canadian forces on 9th April 1917 near Arras. Maurice and the crew of Tank C39 were charged with advancing towards a particular German stronghold, known as the Harp. Tank C39 was a Mark II tank, designed for training purposes and fitted with only unhardened armour. They were never meant for combat but with the delay of the Mark IV a number were used in the Battle of Arras. What happened is described in David Fletcher's book ‘Tanks and Trenches’. 2nd Lt Cameron (C39) found a gap in the attack where the infantry had lost touch. He engaged the enemy with Lewis gun fire until the infantry had time to come up and consolidate. During this time he routed an enemy machine gun crew and captured their gun. A little later the tank received a direct hit, killing one and wounding three of the crew. After attending to the wounded, Lt Cameron handed five of his Lewis guns and ammunition to the infantry. The man killed was Maurice Carter Voile and his comrades buried him near where he fell. Despite the gains of the first day the British were unable to exploit the situation and force a major breakthrough. Eventually the ground that had been gained on 9th April, with the exception of Vimy Ridge, was recaptured by the Germans.

After the war Maurice’s body was moved to its final resting place at the British Cemetery at Tilloy-Les-Mofflaines where the grave is maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.