Food in England is a treasure-chest of marvellous, personally-researched and idiosyncratically-ordered recipes, old customs, ways of growing food, etc, and I consumed it at the rate of a page or two a night - slow reading, if you like. I’ve usually got a selection of books going at any time - a novel, a non-fiction, a spiritual readings book, and, the last year or so, a vintage Ladybird book - a four-course meal for bookworms!

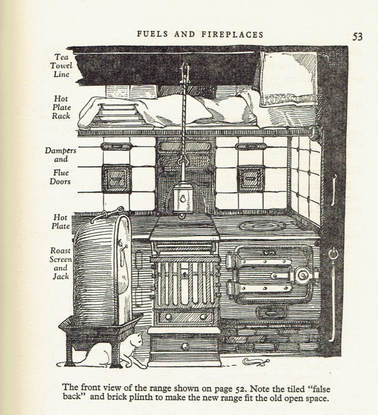

Here’s a baker's dozen of fascinating tasters from the book which might tempt you to acquire a copy. The beautiful illustrations are by Miss Hartley herself (a fact I was unaware of until I finished the book and researched the author - among my jotted reading notes I find the indignant remark - ‘artist not credited!’).

- The history of white bread, and the pre-Reformation belief in the power of consecrated bread.

- Thumb bread ... the American word "piecing" for a snack taken in the hand, has been preserved since it left England with the Pilgrim Fathers. In Yorkshire they still speak of a "piece poke" for a dinner bag.

- Recipe for 18th century Coconut Bread and for Famine Bread (from Markham, ingredients including Sarrasins corne , or Saracen's Corn).

- Description, from sixteenth century journal, of a sea-voyage when the sailors came upon a fifty year old gibbet, used to hang mutineers, from which their cooper made drinking tankards for those "as would drink in them".

- Description of the Welsh pig: “... this old-fashioned, peaceable, capable, thrifty, neat little porker ... has been kept by every Welsh miner, quarryman, and farmer, for centuries.”

- Ox-rein for Clockmakers - the long testicle cord of the bull ... was hung from a hook with a heay weight to stretch it out. Its strong gut texture was used as pulleys in some sorts of grandfather clocks.

- The famine years of the Middle Ages - ‘To realise how desperate was the famine you must know the seasons as the starving peasants knew them - close and vital knowledge.’

- A recipe for Mediaeval Chewing-Gum (or chewing wax) using beeswax, honey, ginger and cinnamon

- The middle-class Victorian household 1800-1900 section includes mention of brisk exercise before breakfast, which brought to mind the old ladies I met when I was alumni officer at the boarding-school where Enid Blyton's daughters were educated. Girls in the 1920s and 1930s were required to run to the village and back (3 miles!) before breakfast every day.

- The Hafod, or summer farm in early times, common to all mountain countries (now no longer practised in Wales, sadly)

- The old Welsh dog power churn wheel ("It is no hardship, the dogs turn up their job as gladly as their fellows turn up for their job with the sheep").

- The Queen's Cheese recipe (1600), to be made between Michaelmas and Allhallowtide, and a huge cheese, nine feet in circumference, made in 1841 for Queen Victoria from one milking of 737 cows.

- Last but not least, for fellow diehard fans of Patrick O'Brian's Aubrey and Maturin novels - the recipe for soup squares, surely Dr Maturin's portable soup!

I look forward to foraging in second-hand bookshops for her other works - Life & Work of the People of England (6 volumes) sounds right up my street.

Link to clips from a BBC film made by Lucy Worsley:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p010fsbq

RSS Feed

RSS Feed