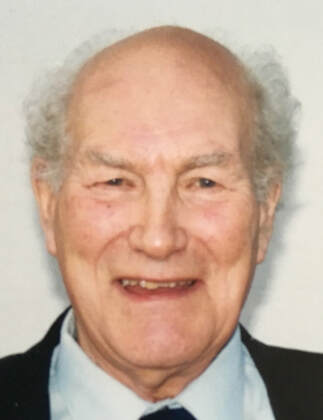

Sadly, although I did once encounter Walter, I missed the chance to get to know a truly memorable man. He had knocked on our door canvassing for the Labour Party. I told him that my husband and I had always voted Labour, but that in the light of Tony Blair having led Britain into the Iraq War by relying on flawed intelligence (and against the wishes of the majority of the British people, including those of us who took to the streets in unprecedented numbers to protest) we came to the conclusion that we could not in all conscience vote Labour in the next election. Walter was quite noticeably distressed at this, and said he too opposed the War, and Tony Blair, but that the body of the party was greater than one man. For some time afterwards, Walter posted copies of the Labour Party newspaper through our letterbox.

I thought of Walter again, recently, when I reflected that a man like him, whose values and principles underpinned a lifetime of service to the many, not the few, and core Labour till the day he died, would surely be a supporter, were he alive today, of Jeremy Corbyn.

Walter was born in North London in 1920, and left school at 14. He cycled 14 miles daily to and from work in the rubber industry at Kingston-upon-Thames. At 16, he wanted to go to Spain to fight with the communist forces opposing Franco's fascists, but was prevented by his mother, who judged him too young.

During the Second World War he served with the Royal Engineers in the 20th Bomb Disposal Division, and travelled around Kent clearing mines and disposing of unexploded bombs and shells. The work, and the death of many of his comrades left an enduring mark on him. He met his wife Joyce in 1941 when he was stationed in Tunbridge Wells. Walter was awarded a medal for his six years in bomb disposal, having continued this dangerous work for two years after the war. The family moved to a council flat in Islington after demobilisation in 1947, and the lack of affordable housing at the time fostered Walter's belief in the need for social housing. During an interview in 2002 he said "having a decent home is the basis of a good society". He was also a vocal advocate for the National Health Service, having been a witness to its birth.

After moving to Seal, in Kent, and later Southborough, his day job was with Cable and Wireless as a telegraph operator and then with the Department of Health and Social Security, but it was in his spare time that, throughout his long life, Walter dedicated himself to working for the welfare of others, including the following:

- active member of the Labour Party

- Parish Councillor

- PTA, Scouts, Tenants' Association supporter

- Town and Borough Councillor

- Branch Chairman, Secretary and Conference Delegate, British Legion

- active supporter of Age Concern

- Chair of the Pensioners' Association

- Southborough Town Mayor

Walter was respected by members from all parties in local politics, and was renowned for his kindness, social conscience and straightforward opinions. He was well-known for his letter-writing efforts. In 1990 he hit the headlines when his anger at Margaret Thatcher's imposition of the flat-rate Community Charge (aka the Poll Tax) led to an appearance before local magistrates (his first ever!) for refusing to pay. He said "It was a bad law, and caused great hardship to so many people. I had to speak up on their behalf. It would have been easy just to pay, but I felt I had to go and speak up, I couldn't funk it." To further ram home his point in this fight which he could not win, he wore his war medals to underline his loyalty to those things in which he did believe.

In early 2003, Walter wrote to the Queen asking her to halt the attack on Iraq, and Britain "being dragged to war by the USA." He was a staunch republican, and was disappointed by what he saw as the bland reply from the Queen's Chief Correspondent Officer. He vowed to write again to the Queen, saying that he thought the situation "too serious to wash your hands of."

Walter was also deeply concerned with environmental issues, and his daughter Coral recalled that even as a youth, he would take home stray animals. In Southborough he campaigned successfully for the establishment of a local nature reserve, Barnett's Wood, plus a rolling tree-planting programme. Every year in all weathers he would go out to save migrating frogs from being killed on the roads adjoining the grass around Holden Pond, their ancient spring breeding grounds. He was also a keen supporter of the Kent High Weald environmental project. Walter never owned a car, but instead used a bicycle and public transport to get around.

Walter described himself as a Christian Socialist, and held the view that he should help those in need. But he was no holier-than-thou stuffed shirt, clearly. Martin Betts recalls: "Walter loved people and he loved life... he laughed a lot - particularly at his own expense - and had that rare gift of making people feel good about themselves and had an amazing number of friends." He kept fit by swimming and weight-lifting, and described himself during a BBC interview, when he was identified as the oldest serving Councillor in Kent, as "a recycled teenager ... inside an old bloke is a young bloke trying to get out!"

Walter died on 21 December, 2003 following a stroke. On the day of his stroke, he was planning to distribute funds to pensioners for Christmas.

Sources:

Press clippings collected by Maxwell Macfarlane, President Southborough Society

Obituary by Martin Betts, Southborough Labour Party

Obituary, Kent Courier, 2 January 2004

Warwick Diary by Jane Bakowski, Kent Courier, 15 March 2013

RSS Feed

RSS Feed